Criticism

Media

Zvonimir Matich: “I show the abstract sense of beauty”

The painter and multidisciplinary artist talks about his latest work, the Luna series.

After exhibiting in Madrid and Barcelona, Zvonimir Matich reflects on his latest work, which emerged after witnessing the enchantment of an eclipse. A natural phenomenon as intense as it is fascinatingly explored through stucco, the painter's signature technique.

Stucco, an unusual technique in painting

More commonly associated with architecture, stucco is an unusual technique in the artistic world. But Matich has been working with it for more than 20 years. "I discovered it thanks to an interior designer friend," says the artist, whose name is Croatian but who was born in Zaragoza.

"I place the stucco on a cloth and, while it's still wet, I add the powdered pigments. Then, using sponges or spatulas, I press the pigments into the stucco and build up layers, adding and removing," the painter explains.

"It's difficult to work with at first, but once you master the technique, everything becomes easier. While with oil you have to wait a long time for it to dry, stucco dries in about 30 minutes. This allows you to add or remove layers without any problems," he explains. He confirms: "What I like about the stucco technique is the chromatic ranges of the colors I mix."

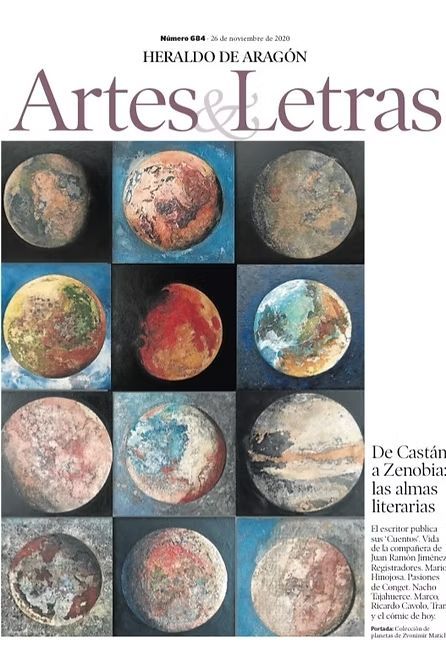

The Luna collection is composed of a universe that evokes unique sensations. The paintings invite you to immerse yourself in their three-dimensional effect, a characteristic that is revealed as the viewer approaches the work.

Traveling, fertile ground for inspiration

"Normally, when creating a collection, I'm inspired by the trips I take." This is where most of his works, such as the "Africa" and "Asia" series, have emerged. All of them have been exhibited in various galleries around the world. Traveling is a trait that Matich carries in his DNA, as much as his early approach to the artistic world. One of his sisters is a painter, another a playwright; his mother painted extraordinarily well at home, and his father was a cultural councilor in Zaragoza.

“The first thing I did when I was a little over twenty was travel around Europe and visit its museums,” explains the painter, who dropped out of medical school to study Fine Arts in Barcelona.

Over time, he has turned the photographs he takes of the landscapes and cities he visits into a record of his own artistic expression and the expansion of his creativity. “When I travel, I take photos, and when I get to the studio, I take in what I see, experience, and begin to work on it,” he says.

The aesthetic value of a work

Zvonimir Matich has his home and studio in the Poblenou neighborhood of Barcelona, where he has lived for over 25 years. And a city that has also witnessed his evolution. Back in the 1990s, "Barcelona was a major artistic hub, and back then I was doing installations in galleries," explains the multidisciplinary artist.

Antoni Tàpies and Miquel Barceló, and especially his works involving cement and sand, are some of his inspirations. However, he confirms that it was the refinement of stucco that led him to express his own connection with this technique. An evolution that is also reflected in his approach to abstract art, which takes on forms according to the need for expression.

For the artist, there's an innate component that a work must present. "I don't understand a work if it doesn't have aesthetic value. Aesthetics understood as something beautiful, with proportions, that makes you admire, that draws your attention even if it's negative... Aesthetics as the result of elaborate work," he says. And this leads to his next statement: "I show the abstract sense of beauty."

Her next project? "I'd like to travel through Iran, Georgia, and Armenia," she says. She's also preparing to launch her new website. In the meantime, you can see her work or explore her 3D studio here.

Jasmine Castresana,

in category ART June 12, 2018

Zvonimir Matich, Paleontologist of the Mind

In analyzing the human perceptual system, Roman Gubern defined the iconic drive as the natural impulse to impose a certain order on the cognitive magma, that is, to reduce reality to shared symbols. But paradoxically, the symbolic image often becomes labyrinthine and cryptic, as occurs in the iconography derived from Hermetic traditions.

This atavistic struggle between the iconic impulse and the desire to preserve the enigma is somehow expressed in the paintings of Zvonimir Matich, where fragments of an intercultural lexicon are sedimented like relics of rock art on strata of eroded matter.

Impressions of the African savannah are captured in the form of zebras, monkeys and elephants emerging from rough surfaces whose cracks recall the gaps in memory, and whose rusty patina is a reflection of the mixtures of memory, sensation and imagination.

It blurs the boundaries between nature and language, sometimes manifesting as cosmic power through organic membranes resembling water waves, sap flows, or fiery spirals.

At other times, we seem to be admiring the ancient paintings that decorate the Ajanta Caves. It matters little whether Matich visited this or other sanctuaries during his travels through Asia, for what remains is the sensory and spiritual assimilation of an ancestral cadence. Something of the exquisite sensuality of the lives of Buddha narrated in these Indian caves is evident in the series Matich dedicates to Asian cultures, but the story itself disappears in favor of the pure psychic imprint, in a process of purification in which the figure is often engulfed by the pure sensorial lava.

The red series might evoke the characteristic Pompeian red of the Villa di Boscoreale. And just as Pompeian frescoes, naturally preserved by volcanic ash, are the expression of a frozen time, Zvonimir's paintings also open a door for us to enter the tunnel of time.

The artisanal treatment Matich subjects the canvases to, with sgraffito painted over layers of pigmented stucco, is in itself a metaphorical reconstruction not only of cognitive mechanisms and the layers of memory, but also of ancient fresco painting techniques. However, the artist is not interested in reproducing mural techniques but rather in transforming these ancient paintings into vestiges sublimated by their ruined condition.

Traces of shared memory, inextricable from personal memories and experiences, which give rise to purely mental images.

Anna Adell

By anaad / In Current Art November 13, 2013

"Every word is a landscape."

Henri Michaux says this in A Barbarian in Asia, when speaking of Chinese poetry. No matter how brief a Chinese poem may seem, the visual information its ideograms contain is extensive and kaleidoscopic, bordering on infinity. The word "blue," he explains, contains the symbols for splitting wood, water, and silk. Zvonimir Matich has also traveled through Asia as Michaux has, and his kaleidoscopic vision has returned with him, fertilized and reconstituted by the vitamins of otherness, which require exposure to the elements, the sun, to be activated. Direct experience. Myanmar, formerly Burma, was a place of pilgrimage for the artist, and more recently, Mongolia and China, from the Gobi Desert to emerging cities, where skyscrapers proliferate and the semiotic jungle grows.

The titles of his most recent paintings bear references to these places and, for that reason alone, whet the appetite and the imagination: Ping'an, Qiaotou, Lijiang, Khatgal, Chuwsgul Lake. "Every word is a landscape," we said. But Zvonimir Matich is not a Chinese poet, but a European painter. He demands certain material proofs of the existence of things. Just as Saint Thomas demanded touching to believe, painting demands, in him, the materialization, if not the carnality of the sensible. The multiplicity of referents for abstract ideas manifests itself, physically, in a development of strata, colors, and forms that are discovered beneath one another, as a product of apparent chance or the measured and wise necessity of geology.

In his mission, the painter is aided by his extraordinary technique, well-honed over the years, which performs wonders with stucco and pigments. The word "blue," the Chinese ideogram, contains the rustle of silk, the smoothness of water, and the work of a woodcutter. All at once. A painting as material as Zvonimir Matich's poses the same challenge of synchronicity. His red series is monochromatic yet multiple in its meanings: the red of oriental lacquer, of the seals with which painters sign their names, and the color of cinnabar. And the color of blood, of course. He is telling us a story of passion and a geological romance at the same time. A premonition, also, of the journey to China he would undertake upon completing the series. The problem of time has been resolved in various ways throughout the history of art. In a single painting, by painters like El Greco, several chapters of the same story could coexist. The Garden of Earthly Delights shows us the life of antediluvian mankind, their perpetual orgy. By closing the doors of the triptych, what Bosch shows us is how everything was left after the waters receded. This grisaille painting shows the world as a place conducive to the excavation and paleontology of existence, life, and even guilt. The color that appears, surprisingly, in Zvonimir Matich's late paintings comes from a laborious excavation, struggling against time, on the grisaille surface of the pure earth, in the telluric aridity of oblivion. His travels are there, and there are the gazes of the people and their clothes and the blue that the lakes inherit from the Mongolian sky.

These aforementioned journeys are a constant in the artist's life, one who never stops. Suddenly, a message from Zvonimir pops up in his email. He's found an internet café in Ulan Bator and took the opportunity to send me his greetings. On another occasion, he sent you a photo from Tanzania. He has also traveled through North America, its unspoiled landscapes, but also its cities. New York, where he lived for six months, Chicago, Miami, Seattle, San Francisco. And South America: Bolivia, Chile, Argentina, Peru... He has a certain predilection, however, for the deserts he collects: the Gobi, the Atacama Desert, which he confessed to me was indescribable. Hence the need for painting, as a means of presentation rather than representation. These travels and these landscapes have also brought him closer to the soul of the people, to the Mongolian shepherds, with whom he lived for a few days, sharing "their food and their songs," and allowing himself to be amazed by the generosity of the nomad.

Zvonimir and I have known each other since we were children. Back then, though he doesn't know it, I wrote a story in which my protagonist visited a lake in Mongolia where dinosaurs bathed. He's been there, but I was there first, even if only in my imagination. The memories he brings back from the place confirm some of my dreams, including the existence of the great dinosaurs, whose remains emerge in his paintings. The shadows of animals, elephants, and zebras, also emerge in his African-inspired paintings. These are Asian steppes or internalized African savannas, which we all carry within us, as if in dreams, and which is why we all find ourselves reflected in Zvonimir Matich's paintings.

Alejandro J. Ratia Zaragoza,

February 2008

Do you have questions about my work?

Contact

Interested in a unique piece or a personalized quote? Let's talk. I'm available for any questions or art projects.